4–8 WEEKS OF TRAINING

Kidney Transplant

When kidney function is almost completely compromised, this is called end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Patients with ESRD require either dialysis or a kidney transplant to stay alive.

While dialysis is the more conservative mode of treatment, a transplant gives kidney patients a chance at a better quality of life. It’s the closest modern medicine can come to restoring natural kidney function.

But it’s also a major surgery. This means it comes with risks and costs that every patient should consider. Below you’ll find an overview of what’s involved in a kidney transplant.

The Procedure

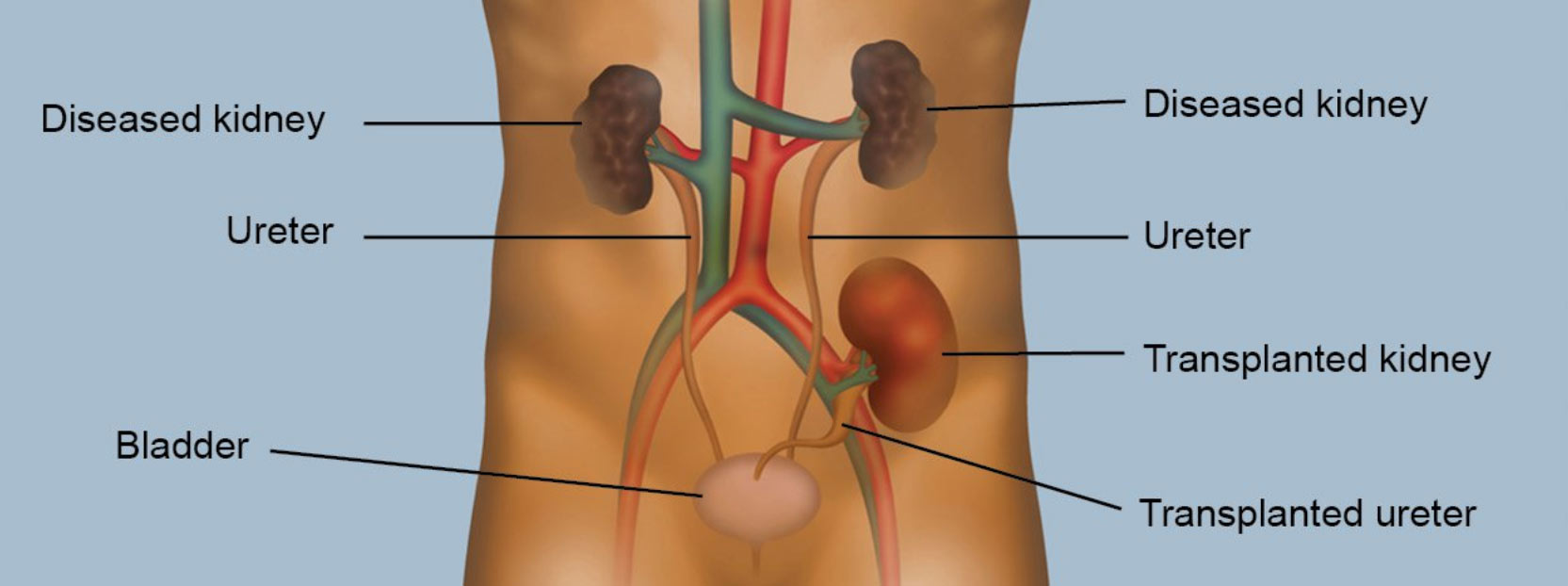

During this major surgical procedure, patients with renal failure will receive a new, healthy kidney from a donor. The donor can be living, or recently deceased..

During this major surgical procedure, patients with renal failure will receive a new, healthy kidney from a donor.The donor can be living, or recently deceased.

The transplanted kidney will be placed in your abdomen, and connected to your body’s blood vessels and bladder. If the surgery is successful, it will take over functions from the failed kidneys, including producing urine and filtering blood. Your two original kidneys, meanwhile, will remain in place, unless they’re causing secondary issues like infection or hypertension. For your body to accept the new organ, you will need to take immunosuppressant drugs. These help revent your immune system from rejecting the new kidney, and will be required for the rest of your life.

Pros and Cons

When successful, transplants can dramatically improve quality of life. Patients have more energy, feel less sick, and can have less restrictive diets. They will also not have to worry about dialysis treatments.

But, as with any surgery, there are potential risks. They include:

Rejection—despite immunosuppressants, your body may still reject the new organ. Most rejections are mild, not permanent, and occur within the first six months of the transplant. But, although rare, chronic rejection is possible, and will result in loss of the new kidney.

Kidney failure—Your new kidney may not function immediately after the transplant, or else fail after a number of years inside you. This may require you to go back on

dialysis, or else get a new transplant.

Cancer—Immunosuppression makes your body less able to detect cancer cells, and fight off infections that are associated with certain cancers. This increases your risk of developing cancer.

The transplant itself also comes with potential side effects:

- Blood clots

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Weight gain

- Hypertension

- Narrowing of the renal artery

To obtain a transplant, you will need two things: approval from a physician and a donor.

Your doctor will not only need to confirm the extent of your kidney trouble, but will also need to decide if you’re healthy enough for surgery. This will entail a complete medical exam and several tests to ensure you can withstand the stresses of a major operation.

Timing is also an important factor in the procedure’s success. Generally, the sooner you can get one, the better. However, it’s also important to remember that, unless you find a willing volunteer, the average wait time for a healthy kidney is between 3-5 years. Often this means that you will need to be on dialysis while you wait.

Hemodialysis

If you’d prefer not to travel to a dialysis center, hemodialysis can be performed at home.

The hemodialysis process extracts blood from your body and passes it through a dialyzer — a special membrane that functions like an artificial kidney — which cleans and chemically balances it. The clean and healthy blood is then returned to your body, where it goes back into circulation.

(For more about connecting your body to a dialyzer, see the ‘Dialysis Access’ section.)

At-home hemodialysis allows more flexibility and comfort for your treatments, and helps you save time and travel costs. It can be done anywhere from 3 to 5 times per week, depending on what your doctor recommends. You will have access to an on-call nurse over the phone in case any questions or concerns arise.

But having hemodialysis at home means you won’t have a dialysis center’s staff to help you. You will have to manage some aspects of the treatment yourself.

TO RECEIVE HEMODIALYSIS IN YOUR HOME, YOU WILL NEED SEVERAL THINGS:

A RELIABLE CARE PARTNER

(Like a family member or friend who can accommodate your dialysis schedule)

AN INSPECTION OF YOUR PLUMBING AND ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS

A PLACE IN YOUR HOME FOR SUPPLIES AND EQUIPMENT

Peritoneal Dialysis

(“Peritoneum” = abdominal lining; “Dialysis” = “Filter”)

Unlike hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis (PD) is always performed at home. PD uses the natural membrane from the lining of your abdomen — called the peritoneum — to get the filtering done. PD has a number of advantages to hemodialysis. You can do PD anywhere clean and dry — including at home, while travelling, or even in a car (although this is usually not advisable).

It’s also a continuous process, much like the filtering done by healthy kidneys. This makes it gentler on your body.

The training for PD is much less extensive than hemodialysis training. It involves learning hygiene and maintenance for your catheter, and proper disposal of medical waste. All told, it can be finished in a week or two.

Follow-up is also relatively easy — you’ll be checking in with your kidney care team once or twice per month.

And, barring previous medical issues with the abdomen, most patients are good candidates for it. But as always, the decision about what kind of dialysis to pursue is between you and your doctor.

Performing Peritoneal Dialysis

To prepare your body for peritoneal dialysis, you will need surgery to insert a catheter into your abdomen. This catheter will give you the access you need to manage treatment.

During PD, you use the catheter to fill your abdomen with a fluid called dialysate. This fluid, full of a sugar called dextrose, will draw waste and fluid from your blood through the peritoneal lining.

Then, you will use your catheter to extract the waste-filled fluid from your abdomen, and replace it with clean dialysate. After that the cycle begins again.

These cycles are called exchanges. How these exchanges are done depends on which type of PD you and your doctor choose — Continuous Cycler-Assisted Peritoneal Dialysis (CCPD), or Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD)

CCPD

Continuous Cycler-Assisted Peritoneal Dialysis (CCPD) happens while you sleep. It involves connecting your catheter to a machine called a cycler, which takes care of dialysate exchanges for you.

The cycler will typically run 3-5 exchanges, over the course of 9 hours each night. In the morning, the cycler will finish its work by filling your abdomen with fresh dialysate. This will remain in your abdomen for the entire day. Then, when it’s time to go to bed, you will hook yourself up to the cycler again.

CAPD

By contrast, you perform Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD) by hand.

For each cycle, you will hang a bag of dialysate above the level of the catheter, and let gravity do the work to draw the fluid into your abdomen. Then, after the dialysate has done its work, you will drain the fluid into a waste bag below you. The entire process takes 30-40 minutes.

Your doctor will tell you how many exchanges you should do each day, and how long you should let the dialysate sit in your abdomen for each session.

CAPD may be a good idea if you’re a light sleeper. Before you go to bed, you’ll fill your body with fresh dialysate. It will sit in your abdomen all night long — with no need to perform any cycling or hook yourself up to a machine.

Hemodialysis

“Hemo” = “blood”, “dialysis” = “filter”

Hemodialysis is the only type of dialysis performed in dialysis centers.

The hemodialysis process extracts blood from your body and passes it through a dialyzer — a membrane that acts as an artificial kidney — which filters, cleans, and chemically balances it. The clean and healthy blood is then returned to your body, where it goes back into circulation.

(For more about connecting your body to a dialyzer, see the ‘Dialysis Access’ section.)

Having dialysis performed in a center comes with a number of helpful benefits.

Dialysis is a slow, gradual process that requires a consistent time commitment. More than likely, your in-center dialysis treatment will involve at least 3 sessions per week, typically lasting 3-4 hours each (although they can be longer).

While arranging transportation and travel-time are concerns, schedules for in-center dialysis are very flexible. They can happen during the day, or even overnight.

In a dialysis center, much of the treatment will be done for you. Nurses and other clinical staff will monitor your progress and your condition, and you can consult them on any concerns you have about your health.

And, unlike with at-home dialysis, dialysis performed in-center requires minimal training. You won’t have to go anywhere else for labs or checkups, and you will also not have to worry about storing or managing any equipment.

Having dialysis performed in a center comes with a number of helpful benefits.

Dialysis is a slow, gradual process that requires a consistent time commitment. More than likely, your in-center dialysis treatment will involve at least 3 sessions per week, lasting 3-4 hours each.

While arranging transportation and travel-time are concerns, schedules for in-center dialysis are very flexible. They can happen during the day, or even overnight.

In a dialysis center, much of the treatment will be done for you. Nurses and other clinical staff will monitor your progress and your condition, and you can simply sit and allow them to do their work.

No matter what type of dialysis treatment you choose, you will need to connect your body to some kind of external equipment. This means you will have to undergo surgery.

While these procedures are very common and routine, every procedure comes with risks. You should consult your physician about which surgical options are best for you.

For Hemodialysis

There are three options for connecting a dialyzer to your bloodstream:

FISTULA

To prepare your body for dialysis, a surgeon will create an arteriovenous fistula — a connection between an artery and a vein — in your arm. Following surgery, it will take weeks to months for the fistula to be ready for dialysis treatment.

During treatment, your dialysis nurse will insert two needles into the fistula. One needle will withdraw blood into the machine, and the other will return the blood after it has been filtered.

This is considered the best possible option, as it provides optimal blood flow and carries a very low risk for infection.

GRAFT

If you’re not a candidate for a fistula, a graft works on a similar principle. However, instead of connecting an artery and vein already inside your body, a graft connects them with a soft artificial tube.

Patients might need a graft if the blood vessels in their arms are compromised by prior medical issues.

PORT

A catheter entails inserting a tube (or port) through your neck, chest, or groin and into a central vein — one that connects directly into your heart. This tube then splits into a y-shaped branch that connects to the dialysis machine.

This is the most invasive option, and also the least efficient. The rate of blood flow through a catheter is slower than through a fistula or a graft, making each treatment session take longer to complete.

Some patients with weakened blood vessels may have to rely on a catheter for the duration of their treatment. However, ports are the least preferred method of access, as they come with a much higher risk for mortality and complications.

For Peritoneal Dialysis — Catheter Insertion

A peritoneal catheter is a soft tube running into your abdomen or your chest. It gives you the access you need for peritoneal dialysis treatment. Inserting it is typically a short, painless procedure.

As with most surgeries, however, you may feel a little pain after the procedure. You may also feel groggy or nauseous from the anesthesia. But most patients recover fast, and they quickly get used to having the catheter tube.